How come all my body parts so nicely fit together?

All my organs doing their jobs, no help from me!

A person pulls a spider's leg out

To watch it keep on moving and twitching.

— “How Does a Duck Know?”, Crash Test Dummies

Surely you’ve heard the word “galvanized.” You may know it best from its figurative meaning first recorded in 1853 meaning to “shock or excite,” as in galvanizing someone into action. But in homebuilding you’ll find it most often in reference to the galvanization of metal. Most plumbers I’ve met refer to “galvanized” metals as “galvi” (GAL-vee), as in “galvi” (galvanized) metal pipe and “galvi” nails, among others.

Galvanization, in the metallurgical sense, is a process by which a metal such as steel or iron is coated with zinc in order to protect it from rusting. The zinc acts as a sacrificial anode — and no, I don’t expect you to know what that means, and I’m not going to explain it. Because, you see, I want to tell you about Luigi.

It’s-a me, Metal Luigi

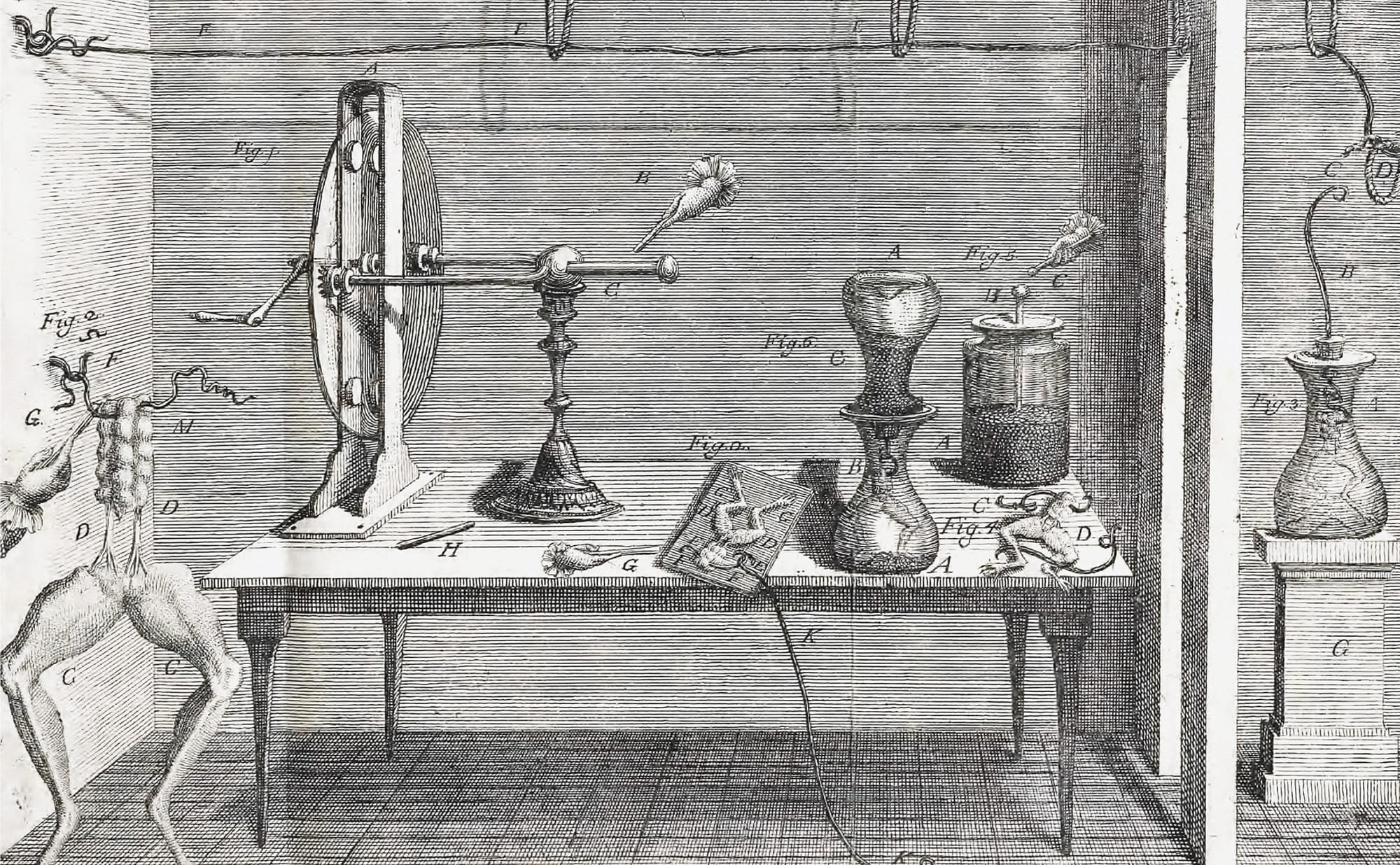

In 18th-century Bologna, in northern Italy, there was a physicist who specialized in bioelectromagnetics, the study of interactions between electromagnetic fields and biological systems. One day he was messing around frog legs (as you do, in 18th-century Italy), and — in addition to inadvertently birthing the modern notion of bioelectricity — this physicist discovered something else.

You see, he had these little ribbity legs on a brass hook and, quite to his surprise, they suddenly twitched when he placed his scalpel into them — despite there being no electrical connection wired anywhere nearby.

This man’s name was Luigi Galvani. Luigi. Galvani. Galvaaaaaannnnni.

Are you getting it?

The volta

One of Galvani’s contemporaries, Alessandro Volta, disagreed with Galvani’s premise that the current resulted from the frog’s innate “animal electricity,” and hypothesized that the current which caused the frog legs to twitch arose from the interaction of two metals with the presence of an electrolyte (such as water).

Volta’s hypothesis led him to the invention of the voltaic pile, an early form of an electric battery. And, in the mind-blowing tradition of namesakes, Volta is where we get the electrical term “volt.”

This turn of events, which led to much of our modern battery technology, wasn’t a direct line to modern methods of galvanization, but it did improve our understanding of how metals behave in the presence of electrolytes.

It’s not what you zinc

Although there is no single inventor of the process of galvanization, Sir Humphry Davy, a 19th-century British chemist is credited with being one of the first to experiment with the protective qualities of zinc when applied to other metals.

The process of dipping steel or iron objects in molten zinc for industrial purposes was eventually patented by French chemist Stanislas Sorel in 1837, and French engineer Paul-Jacques Malouin patented a similar process in 1838.

But the birth of the galvanization process all began with Galvani’s experiments with frog legs in 1786, half a century earlier. Today, in homebuilding, all manner of galvanized materials, from sheet metal flashing, to pipes and nails are employed to help construct buildings. The protective zinc coating acts the first line of defense so that, when it comes into contact with moisture, causes the zinc to corrode rather than the steel or iron underneath.

So, when you hear — or use — the word “galvanized,” or “galvi,” remember that it’s old Luigi’s name you’re invoking. Luigi Galvaaaani.